Ronnie Spector

In recent months, my toddler has assumed a number of alter egos. He is eclectic in his tastes, though they mostly tend toward musicians. Bob Dylan. Ringo Starr. Millo Castro Zaldarriaga (a pioneering female drummer in 1930s Cuba).

The alter ego with the most longevity, however, has been the ‘60s rockstar Ronnie Spector. She has captured his imagination and his heart. He has performed concerts as Ronnie, assigning my husband and me the roles of her two backup singers, Estelle and Nedra. He sometimes asks me to be Ronnie instead and to sing “Be My Baby” to him while he pretends to be a “really tiny baby.” Together, we invent bedtime stories about the adventures he has as – or with – Ronnie.

Ronnie Spector -- my son's rock idol, imaginary friend, and first crush -- performing "Be My Baby" in California, 1965. I have seen this video SO MANY TIMES.

Observing him as he casually, inventively tries on these different identities got me thinking about alter egos for grown-ups.

Can alter egos serve any purpose to us as adults, particularly as we navigate our creative and parental identities?

Can they shake up our patterned ways of thinking? Can they be used productively to stave off other adult forms of escapism – the mid-life crisis, the extra-marital affair?

Anyway, alter egos. Here are two of mine. And, yes, I’ve noticed that they are both single women who opted not to have kids.

Dr. Mae Jemison

In 1992, Dr. Mae Jemison became the first woman of color to go to space, when she went into orbit on the 8-day Endeavour mission.

It’s not like she was just taking it easy before working for NASA: Jemison was a medical doctor, involved in humanitarian missions in Liberia and Sierra Leone. Before that, she earned dual college degrees in chemical engineering and African American studies at Stanford, where she was admitted at age 16. Oh, and she’s also an accomplished dancer.

I admire Jemison’s bravery – the physical and mental courage of venturing out beyond the earth's atmosphere while also navigating through the racist and sexist atmospheres closer to home. But, above all, I admire the self-confidence and sense of purpose that underlies, enables, those risk-taking actions.

In interviews, Jemison talks about how, as a little girl growing up on Chicago’s South Side, she never doubted that she would one day go to space. And, though she is happy to serve as a role model for young girls of color, she thinks that who really needed to see her – and who really needed to hear the countless untold stories of women excelling in STEM – were (and are) the older white men running the show.

I also feel a kindred spirit in Jemison who, like myself, is fascinated by how the arts and sciences can complement each other. She is currently directing the 100 Year Starship project to fund the research advances necessary to achieve interstellar travel. Here’s what Jemison has to say about what inclusivity means to her and why it matters:

What strikes me about Jemison’s confidence, sense of mission, and expansive point of view is that they don’t lead to narcissism and swagger. They instead bring her out of herself, into a global community, into the universe itself.

Dr. Jemison’s example points to the value to others of a life lived with action vs. self-doubting paralysis.

Stevie Nicks

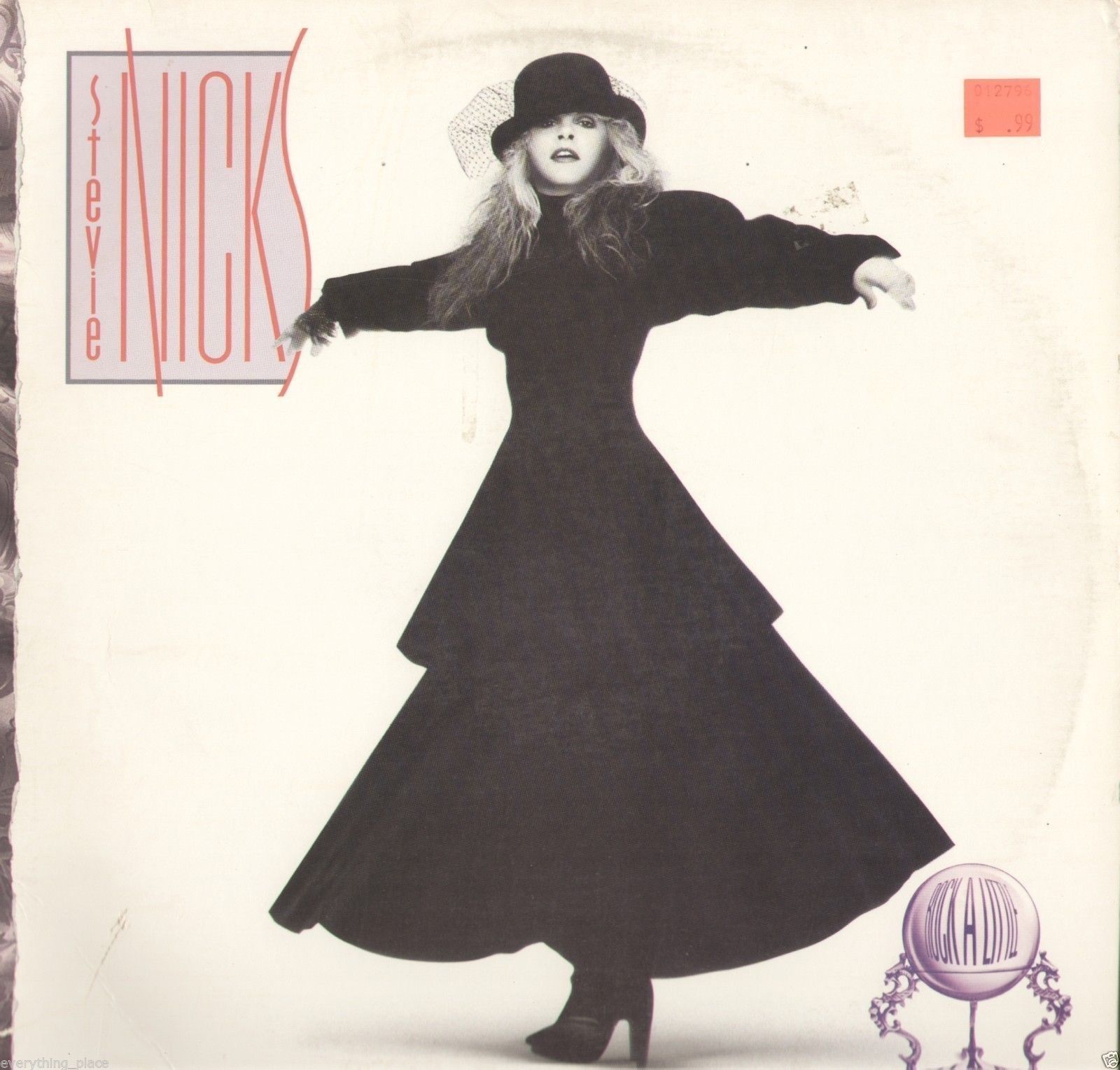

My second alter ego isn't exactly an original choice. Every year, in New York City, there’s a Night of the Thousand Stevies, where partygoers dress up as the musician Stevie Nicks, longtime member of the band Fleetwood Mac as well as a successful solo artist.

Images: Classic Stevie (plus the author as Stevie Nicks, Halloween 2017).

Nicks is certainly more flawed than Jemison. She’s struggled with two major bouts of addiction that nearly killed her. But out of that vulnerability, or offset by it, is the strength of a survivor. As a 4-year-old, she sang duets with her country-musician grandfather, and there's something a little bit country about Stevie's ability to make poetry out of heartbreak.

A lot like my son’s idol Ronnie Spector, who continues to tour into her 70s, Nicks is driven by career and performance and sheer love of singing.

So, what is it about her that makes her such a compelling alter ego? Aside from that strength and self-sufficiency, there’s a magnetism and mystery to Stevie. And, despite being a card-carrying Introvert, part of me is still drawn to the stage, the spotlight.

Jemison and Nicks point me to traits that I admire but possess faintly, if at all. Jemison shows me that the way forward involves embracing some degree of risk; Nicks reveals an often unarticulated desire for attention and acclaim. Stevie's "Gypsy" takes me back to my four-year-old-self, in a gypsy costume, singing and dancing on a makeshift stage.

That doesn’t mean that alter egos aren’t also traps that can reveal our biases. Jemison and Nicks, for example, are beautiful women who have aged gracefully – they both appeared on People’s annual ‘50 most beautiful’ list, in 1993 and 1997, respectively. That desire for feminine beauty is so culturally ingrained, and I believe their physical beauty adds to their allure, helps to rocket them into mythical status.

More generally, Jemison and Nicks’ lives could be taken as evidence that becoming a parent means sacrificing one’s own professional or creative achievement.

Whenever I imagine a life elsewhere or other than this one, that alter ego never has kids or a partner. My imagination strains to envision how that other self - the interesting, cosmopolitan one - could still be interesting and cosmopolitan without remaining fully, richly alone.

Robert Frost

In my first year of graduate school, I was a TA for an American literature survey course. In his opening lecture, the professor went line by line through Robert Frost’s poem “The Road Not Taken.” Frost’s poem has become the emblem of individualism and non-conformity as the ultimate American values.

The professor delighted in exploding this conventional (and incorrect) interpretation of the poem. Because if you read the poem carefully, you’ll find that the” two paths that diverged in a wood” were not all that different. They were both traveled about equally: “the passing there had worn them really about the same,” and “both that morning equally lay / In leaves no step had trodden black.” It’s only “years hence” that the narrator revises history, suggesting that his choice of the road “less traveled by…has made all the difference.”

It’s all about the story.

The stories we tell about parenting are also needlessly limiting. Your life is over after kids. You will never have another adventure again.

Maybe this circles back to the question of how to be unconventional when living a ‘conventional’ life with a partner and children. How do you cultivate a habit of breaking with patterns or received wisdom, which seems essential to creativity in any field, when you are inhabiting the cultural norm of parenting?

But this itself is a simple dichotomy. The two roads – partnered or single, kids or no kids – don’t necessarily have to be opposed. Like Frost’s two roads, they simply represent varied forms of human experience. And both are pioneering, untrodden paths in their own right, with the capacity to be mind- and habit-altering if you allow them to be.